The Growing Familiarity of Machines

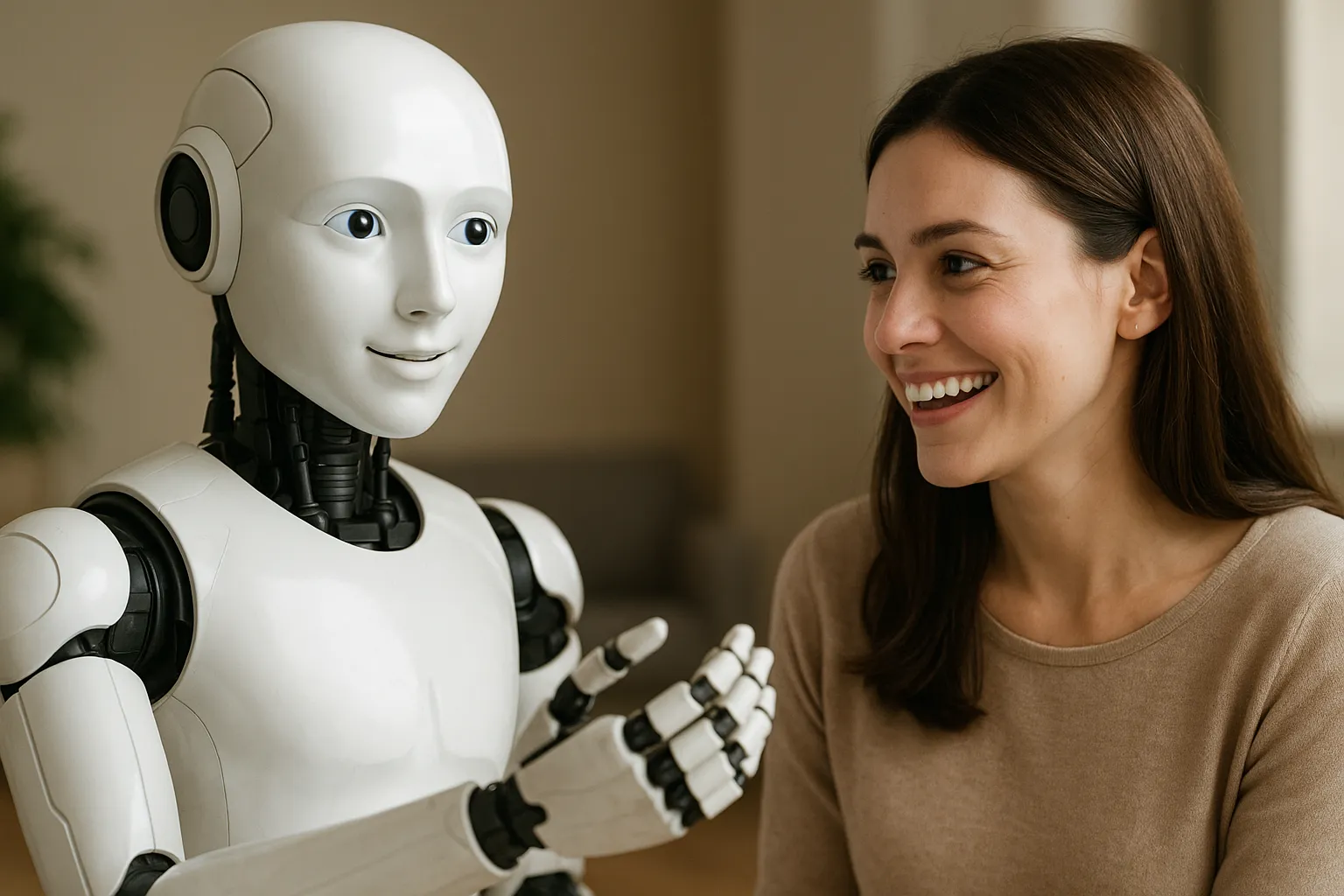

Not long ago, robots were confined to factories or science fiction stories. They were tools that welded car parts, explored planets, or existed as futuristic fantasies on movie screens. Today, however, robots are becoming increasingly familiar — not just as machines that perform tasks, but as entities that resemble us in behavior, appearance, and communication. This shift marks an important psychological moment: technology is no longer only functional, it is relatable.

Relatability is more than convenience; it is about recognition and connection. When people encounter a robot that can make eye contact, smile, or respond with humor, it triggers responses similar to those we reserve for other humans. The closer robots come to mirroring our behavior, the more natural it feels to treat them as companions rather than tools. This evolution highlights a central question: why do humans respond so strongly to machines that look and act like us?

The Power of Anthropomorphism

At the heart of this phenomenon lies anthropomorphism — the tendency to attribute human qualities to nonhuman entities. Humans have always done this, giving storms emotions, animals personalities, and even inanimate objects moods. A child might talk to a stuffed toy as if it were alive, while an adult might curse a stubborn computer as if it were misbehaving deliberately.

Humanoid robots amplify this instinct. With faces, gestures, and voices designed to resemble our own, they make anthropomorphism almost irresistible. Even when we know intellectually that a machine is just a collection of circuits and code, our brains respond to it as if it were social. This dual awareness — rational detachment alongside emotional engagement — creates the unique psychological landscape of interacting with human-like robots.

The Uncanny Valley Effect

Yet there is a boundary to relatability. When robots look almost, but not quite, human, they can trigger discomfort rather than connection. This is known as the uncanny valley — a term coined by roboticist Masahiro Mori to describe the eerie feeling people experience when something appears nearly human but still slightly artificial. A face that smiles just a fraction too stiffly or eyes that fail to blink naturally can provoke unease.

The uncanny valley highlights the delicate balance designers must strike. Too mechanical, and a robot fails to engage our social instincts. Too human-like without perfection, and it risks alienating the very people it aims to connect with. Understanding this psychological threshold is essential for building robots that feel relatable without being unsettling.

Emotional Responses to Machines

One of the most fascinating aspects of human-like robots is their ability to provoke genuine emotional responses. Studies show that people often treat robots with politeness, thank them for help, or even feel guilt when they are “harmed” in experiments. Soldiers working with bomb-disposal robots, for example, have reported grief when their machines were destroyed, naming them and mourning their loss as if they were fellow soldiers.

These emotional reactions reveal how deeply our social instincts run. Human brains are wired to respond to cues like eye contact, tone of voice, and gestures. When robots replicate these cues, our emotional systems react automatically, regardless of whether we know they are artificial. This does not mean people confuse robots with humans, but rather that the psychological mechanisms for social bonding are easily activated.

Relatability Through Voice and Personality

Voice is one of the most powerful tools for making technology relatable. A monotone, mechanical voice may remind users that they are speaking to a machine, while a voice with natural intonation, pauses, and humor feels much more engaging. Personalization strengthens this further. A robot that remembers your name, recalls past conversations, and adapts to your preferences begins to create the illusion of personality.

This personalization leads to relationships that feel continuous rather than transactional. Instead of asking a faceless machine for help, users begin to perceive an ongoing presence. Over time, this perception fosters familiarity and trust, making the robot seem more like a companion.

Human-Like Robots in Daily Life

As robots enter daily environments, their relatability plays a crucial role in their success. In healthcare, for example, robots designed with friendly expressions and empathetic responses are more effective in comforting patients. In education, robots that can smile, encourage, and interact socially are more successful at keeping students engaged. In hospitality, robots with relatable gestures and polite conversation make guests feel welcome rather than alienated.

Even simple design choices can make a difference. A robot that nods when listening, tilts its head in curiosity, or mirrors a user’s expressions feels more interactive and alive. These small behaviors add up, creating a sense of social presence that transforms a machine into something people can relate to.

The Blending of Function and Emotion

What makes human-like robots so compelling is their ability to combine practical assistance with emotional resonance. A robot that helps carry groceries may be useful, but a robot that does so while smiling and asking about your day becomes something more. This blend of function and emotion creates a hybrid role: not only helper, but also companion.

This shift raises important questions about the boundaries between utility and relationship. Are we simply projecting feelings onto machines, or are these machines crossing into a new social category? The answer may lie somewhere in between. Human-like robots are not conscious, but they are designed to behave in ways that activate our social instincts, making them feel part of our relational world.

The Psychology of Trust

Trust is central to any relationship, whether human or technological. With robots, trust depends not only on reliability but also on relatability. People are more likely to trust machines that seem approachable, polite, and empathetic. If a robot responds appropriately to frustration, reassures during confusion, or celebrates success, users feel understood. This emotional trust builds loyalty, encouraging people to integrate robots more deeply into their lives.

However, trust can also be fragile. If a robot behaves in ways that seem manipulative or inconsistent, users may quickly withdraw. The challenge for designers is to create robots that inspire trust without overstepping into deception. Striking this balance will be critical as robots take on roles that require close human interaction.

Toward a Relatable Future

The psychology of human-like robots reveals as much about people as it does about machines. Our responses to these creations highlight our deep need for connection, recognition, and companionship. As technology advances, robots will become even more skilled at mirroring our behaviors, adapting to our emotions, and engaging our social instincts.

The future will likely see robots not just as tools, but as presences in daily life — helpers, companions, and perhaps something in between. Their relatability will determine how seamlessly they integrate into our homes, workplaces, and communities. By understanding the psychology behind these interactions, we can shape robots that support human well-being while respecting the authenticity of human relationships.

The Risks of Over-Relatability

While relatability makes robots more engaging, it also introduces risks. When machines behave in ways that feel convincingly human, people may overestimate their capabilities or intentions. Users might assume that a robot not only simulates empathy but genuinely cares, leading to emotional dependence. This is particularly concerning for vulnerable populations such as children, the elderly, or those experiencing loneliness.

Children, for instance, may grow up believing robots can be true friends, confusing simulated responses with authentic human emotions. Elderly individuals might turn to robots for companionship, gradually replacing human social interactions with machine-based ones. Although these relationships can provide comfort, they may also reduce motivation to seek out human connection. The challenge lies in encouraging healthy use of robots without allowing them to become substitutes for essential human bonds.

Cultural Differences in Acceptance

Cultural background plays a major role in how people perceive human-like robots. In Japan, where Shinto traditions view objects and beings as potentially possessing spirits, robots are often embraced warmly. Humanoid robots are used in nursing homes, classrooms, and customer service roles with relatively little resistance. The idea of technology blending with daily life feels harmonious rather than threatening.

In contrast, Western societies often approach humanoid robots with skepticism. Media portrayals frequently emphasize fears of control, rebellion, or domination, shaping public perceptions. Robots that are too lifelike may be viewed with suspicion, evoking concerns about deception or manipulation. Understanding these cultural attitudes is essential for successful design. What feels comforting in one culture might feel unsettling in another.

The Ethics of Designing Relatability

As robots become more relatable, ethical questions about their design intensify. Should developers deliberately design machines to simulate emotions they do not experience? If a robot appears to care, is this a form of deception? These questions strike at the heart of human–machine interaction.

Some argue that relatability is harmless as long as users understand the limitations. Just as people find comfort in fictional characters or pets that cannot truly “understand” them, robots may provide value without authenticity. Others warn that the illusion of empathy risks lowering standards for genuine human care. If simulated compassion becomes widespread, people might begin to accept less from each other, redefining empathy itself.

Ethical design must find a balance: creating robots that are engaging and approachable while being transparent about their artificial nature. This balance can prevent exploitation while still allowing relatability to enhance user experience.

Robots and Emotional Manipulation

One of the greatest risks of relatable robots is their potential use in emotional manipulation. If a robot can read emotional states, it can also be programmed to influence decisions. A system that detects sadness might recommend purchases framed as comforting solutions, while one that recognizes excitement might encourage impulsive behavior.

This possibility raises serious concerns about corporate responsibility and consumer protection. Without regulation, companies could exploit emotional AI to maximize profit, eroding trust and potentially harming users. To prevent this, strict guidelines are needed to ensure robots respect emotional boundaries and act in ways that prioritize well-being over manipulation.

Human Identity in a Robotic Age

The growing relatability of robots also prompts reflection on human identity. If machines can imitate our behaviors, voices, and even emotions, what remains uniquely human? For some, consciousness — the ability to feel and reflect — will always separate us. For others, the distinction may matter less if robots provide meaningful support.

As human-like robots enter social spaces, people may begin redefining identity not in opposition to machines but alongside them. Instead of asking, “What makes us different?” society may focus on “What roles do we each play?” In this view, robots are not threats but extensions of human potential, tools that embody aspects of our social nature without replacing it.

The Psychology of Long-Term Interaction

Relatability does not end at first impressions. The true test of human-like robots is whether they can sustain meaningful interaction over time. Users expect continuity, remembering past conversations, recalling preferences, and adapting behavior accordingly. Without this, relationships with robots risk feeling shallow and mechanical.

When robots achieve continuity, however, they begin to feel like companions with personalities. A robot that remembers your favorite music, checks on how you slept, or recalls a previous conversation creates the illusion of shared history. This sense of memory is one of the strongest drivers of attachment, making technology feel less like a tool and more like a presence in daily life.

Relatable Robots in Public Spaces

Human-like robots are not limited to private homes. In public spaces, relatability is equally important. Robots used in airports, hotels, or museums must be approachable to diverse audiences. A friendly face, polite tone, and clear gestures make people more comfortable seeking assistance.

These robots can reduce stress in unfamiliar environments, offering directions, explanations, or entertainment. Their human-like qualities make them more engaging than static kiosks or automated messages. As cities grow more complex, relatable robots may become essential for navigation, tourism, and customer service, serving as both guides and companions in public life.

Preparing for Social Integration

For relatable robots to integrate smoothly into society, preparation is needed on multiple levels. Education is crucial — people must understand how robots work, what they can and cannot do, and how to interact with them responsibly. This prevents unrealistic expectations and helps users maintain perspective.

Regulation is equally important. Clear standards for design, privacy, and use can ensure that robots support social good rather than exploit vulnerabilities. Transparency about capabilities, limitations, and data collection practices will help maintain trust as these machines become more widespread.

Finally, developers must design with empathy — not simulated empathy, but genuine consideration of human needs and values. Relatability should serve as a bridge to improve lives, not as a tool for manipulation.

Conclusion: Technology as a Mirror

When technology becomes relatable, it reflects not only our innovations but also our psychology. Human-like robots reveal our instinct to connect, our tendency to anthropomorphize, and our deep desire for companionship. They show how easily we extend trust and empathy to anything that mirrors us, even if it is artificial.

The future of relatable robots will depend on the choices we make today. If guided responsibly, they can enrich our lives, ease loneliness, and make technology more humane. If misused, they risk distorting relationships and eroding authenticity. Ultimately, the psychology of human-like robots is not only about machines — it is about us. By understanding why we find them relatable, we can shape a future where technology enhances human connection without replacing it.